Experiencing Trauma

The directly experienced traumatic event may include:

- Exposure to war as a combatant or civilian

- Actual or threatened physical assault

Being kidnapped or taken hostage - Terrorist attack

- Torture

- Immigration

- Incarceration as a prisoner of war

- Natural or human-made disasters

- Severe motor vehicle accidents

- Being bullied

- Life-threatening medical emergencies

Sexual trauma includes, but is not limited to, actual or threatened sexual violence or coercion. For example:

- Forced sexual penetration, alcohol/drug-facilitated non-consensual sexual penetration, or other unwanted sexual contacts

- Other unwanted non-contact sexual experiences such as being forced to watch pornography, exhibitionism, unwanted photography or videotaping of a sexual nature, or dissemination of sexual photographs or videos

- For children, sexually violent events may include developmentally inappropriate sexual experiences without physical violence or injury

Witnessed Events

Witnessed events include, but are not limited to:

- Observing threatened or severe injury

- Unnatural death

- Physical or sexual abuse of another person

- Domestic violence

- War

- Disaster

Indirect Exposure to Trauma

Indirect exposure through learning about an event is limited to events affecting close relatives or friends that were violent or accidental (i.e., death from natural causes does not qualify).

Such events include:

- Murder

- Violent personal assault

- Combat

- Terrorist attack

- Sexual violence

- Suicide

- Severe accident or injury

Indirect exposure can also occur through photos, videos, and verbal or written accounts. For example, police officers reviewing crime reports or conducting interviews with crime victims, news media members covering traumatic events, and psychotherapists exposed to details of their patients’ traumatic experiences.

Multiple Traumatic Events

Exposure to multiple traumatic events is common and can take many forms.

- Some individuals experience different types of traumatic events at different times (e.g., sexual violence during childhood and natural disaster as adults).

- Others experience the same kind of traumatic event at different times or in a series committed by the same person(s) over an extended period (e.g., child sexual or physical assault; physical or sexual assault by an intimate partner).

- Others may experience similar or different traumatic events during an extended hazardous period, such as deployment or living in a conflict zone.

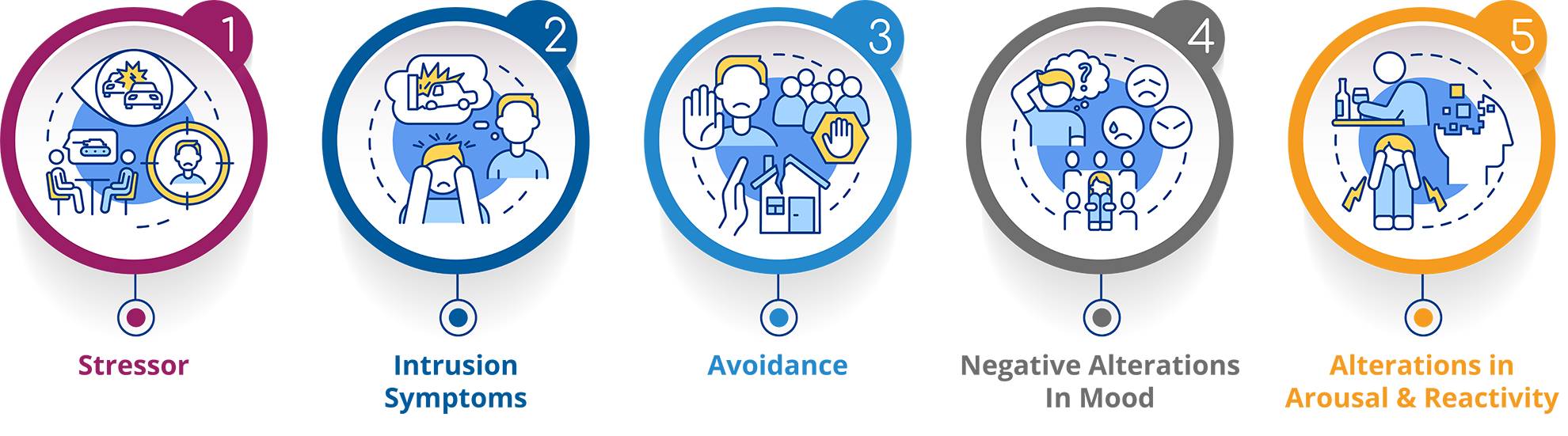

Symptom Clusters

Intrusion

Intrusion

Intrusive recollections in PTSD are distinguished from depressive rumination because they apply only to involuntary and intrusive distressing memories. The emphasis is on recurrent memories of the event that usually include invasive, vivid, sensory, and emotional components that are distressing and not merely ruminative. A common re-experiencing symptom is nightmares of the traumatic event. The individual may experience dissociative states that typically last a few seconds, during which components of the event are re-lived. As a result, the individual behaves as if the event were occurring at that moment. Such events occur on a continuum, ranging from brief visual or other sensory intrusions about part of the traumatic event without loss of reality orientation to a partial loss of awareness of present surroundings to a complete loss of awareness. These episodes often referred to as “flashbacks,” are typically brief but can be associated with prolonged distress and heightened arousal. Intense psychological pain or physiological reactivity often occurs when the individual is exposed to triggering events or somatic reactions that resemble or symbolize an aspect of the traumatic event (e.g., windy days after a hurricane or seeing someone who resembles one’s perpetrator). The triggering cue could also be a physical sensation (e.g., dizziness for survivors of head trauma, rapid heartbeat for a previously traumatized child), particularly for individuals with highly somatic presentations.

Avoidance

Stimuli associated with the trauma are persistently avoided. The individual commonly makes deliberate efforts to avoid thoughts, memories, or feelings (e.g., by utilizing distraction or suppression techniques, including substance use, to prevent internal reminders) and to avoid activities, conversations, objects, situations, or people that arouse recollections of it.Negative Alternations in Cognitions and Mood

- “Bad things will always happen to me.”

- “The world is dangerous, and I can never be adequately protected.”

- “I can’t trust anyone ever again.”

- “My life is permanently ruined.”

- “I have lost any chance for future happiness.”

- “My life will be cut short.”

The individual may experience markedly diminished interest or participation in previously enjoyed activities, feel detached or estranged from other people, or have a persistent inability to feel positive emotions (especially happiness, joy, satisfaction, or feelings associated with intimacy, tenderness, and sexuality). Negative arousal and reactivity alterations also begin or worsen after exposure to the event.

Alternations in Arousal and Reactivity

Individuals with PTSD may exhibit irritable or angry behavior. They may engage in aggressive verbal or physical behavior with little or no provocation (e.g., yelling at people, getting into fights, destroying objects). They may also engage voluntarily in reckless or self-destructive behavior that disregards their physical safety or others. For example, drunk driving, driving at dangerously high speeds, excessive alcohol or drug use, having risky sex, or self-directed violence and suicidal behaviors.

PTSD is often characterized by a heightened vigilance for potential threats, including those related to the traumatic experience and those not associated with the traumatic event. In addition, individuals with PTSD may be very reactive to unexpected stimuli, displaying a heightened startle response, or jumpiness, to loud noises or random movements.

Startle responses are involuntary and automatic; stimuli that evoke exaggerated startle responses need not be related to the traumatic event. Startle responses are distinguished from the cued physiological arousal responses, for which there needs to be at least some conscious appraisal that the stimulus-producing physiological responses are related to the trauma. Concentration difficulties, including difficulty remembering daily events (e.g., forgetting one’s telephone number) or attending to focused tasks (e.g., following a conversation for a sustained period), are commonly reported. Problems with sleep onset and maintenance are common and may be associated with nightmares and safety concerns or generalized elevated arousal that interferes with adequate sleep.

Duration of Symptoms

The diagnosis of PTSD requires that the duration of the symptoms be more than one month. For a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD, there must be a period lasting more than one month during which criteria have been met for the same 1-month period.

Specificers

Because a mental health condition doesn't always present itself in the same way, a DSM specifier can better describe particular scenarios. A significant proportion of individuals with PTSD experience persistent dissociative symptoms. These symptoms include depersonalization, which is feeling detached from their bodies, or derealization, which is feeling disconnected from the world around them. Individuals diagnosed with PTSD with dissociative symptoms receive the diagnostic specifier “with dissociative symptoms” to make the diagnosis more precise.

Associated Features

Developmental regression, such as language loss in young children, may occur. In addition, auditory pseudo-hallucinations can be present, such as having the sensory experience of hearing one’s thoughts spoken in one or more different voices and paranoid ideation.

Following prolonged, repeated, and severe traumatic events (e.g., childhood abuse, torture), the individual may experience difficulties regulating emotions, maintaining stable interpersonal relationships, or dissociative symptoms. When the traumatic event involves the violent death of someone with whom the individual had a close relationship, signs of prolonged grief disorder and PTSD may be present.

Additional Resources

Consider these resources for further insight into Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Blog Posts

Training

- Assessing Allegations of Trauma in Forensic Contexts

- Psychological Evaluation in Personal Injury and Civil Rights Cases

Research