Important legal and clinical issues need to be carefully considered when assessing the competency of a client to represent themselves in court. This is the bottom line of a recently published article in Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. Below is a summary of the research and findings as well as a translation of this research into practice.

Featured Article | Psychology, Public Policy, and Law | 2019, Vol. 25, No. 3, 196–211

Legal and clinical issues regarding the pro se defendant: Guidance for practitioners and policy makers

Author

Christina L. Patton, Colorado Mental Health Institute, Pueblo, Colorado

E. Lea Johnston, University of Florida

Colleen M. Lillard, West Virginia University

Michael J. Vitacco, Augusta University

Abstract

Defendants who attempt to represent themselves, or proceed pro se, make up less than 1% of felony cases. However, when the issue of competency to proceed pro se arises, it can present interesting questions and challenges not only for the defendant, but also for others involved with the trial process. In Indiana v. Edwards (2008), the U.S. Supreme Court permitted states to impose a higher standard of competency for defendants who wish to proceed to trial without an attorney than for defendants who stand trial with representation. States have responded by adopting a patchwork of different, and often vague, competency standards. The current paper describes states’ differing responses to Edwards, courts’ efforts to ensure the constitutionality of those standards, and extant research on the legal standards and guidelines that should apply to forensic evaluators. Drawing upon this body of law and commentary, this article distills principles to guide evaluations of defendants’ pro se competency. To facilitate discussion, this article utilizes three case studies involving defendants with severe mental illness, antisocial personality disorder, and communication impediments unrelated to mental illness. The analysis of these case studies illustrates the application of guiding principles and demonstrates how to distinguish impairments relevant to pro se competence from those that may be legally irrelevant yet still present significant fairness or efficiency concerns.

Keywords

competence to proceed, forensic assessment, pro se competence, forensic evaluation

Summary of the Research

“A 2007 analysis of federal and state databases showed approximately 20% of pro se cases involved a request for a competency evaluation due to potential indications of mental illness. […] at least one study found that pro se defendants are not convicted at a higher rate than those represented by an attorney in state and federal felony cases. […] Proceeding pro se may hold several advantages that are not readily apparent, including the ability to question accusers directly during cross-examination and the possibility of receiving greater flexibility in framing questions on direct examination. In addition, pro se defendants may win sympathy from members of the jury, who could potentially come to view them as the underdog in a “David and Goliath” type of situation.” (pp. 196–197)

“Although representing oneself does offer potential advantages, self-representation in an adversarial courtroom environment can prove to be an ineffective and harmful strategy for many, especially for mentally ill defendants. Mental illness “in the gray zone” (i.e., that which does not undermine competency to stand trial but might render defendants unable to represent themselves) may lead to an inability to prepare and organize an effective defense, difficulty questioning witnesses or mounting a skilled cross-examination, or failure to argue complex points of law.” (p. 197)

“The Edwards Court appeared to limit cognizable deficits to those that stem from a “severe mental illness” (Indiana v. Edwards, 2008, pp. 177–178), and the pro se competency standards of 18 states accordingly only extend to defendants with a disorder of this magnitude. However, Edwards did not define the term “severe mental illness,” and most courts have not attempted to do so. Therefore, whether a particular mental illness may be considered “severe” for purposes of pro se competency is unclear.” (p. 197)

“Allowing mentally ill defendants to proceed to trial without representation runs the risk of compromising the integrity and perceived legitimacy of court proceedings and possibly violating the “moral dignity” of the defendants themselves. On the other hand, depriving individuals with intact decision-making abilities of the right to self-representation risks assaulting their dignity, as well as violating their Sixth Amendment rights. To avoid perpetrating these injustices, the process of evaluating pro se defendants should be informed by both legal precedent and “best practice” clinical strategies.” (p. 197)

“Although the states have undertaken efforts to implement guidelines of pro se competency for legal professionals, forensic evaluators lack practical guidance for conducting competency evaluations where pro se competence is raised, in light of the vague recommendations noted in Edwards. A number of challenges unique to assessing this specific domain exist, including uncertainty about whether more serious charges require a greater level of pro se competency (i.e., whether a defendant charged with murder might have to meet a higher threshold than one facing misdemeanor charges), which basic abilities are needed for self-representation at trial, and how strong these abilities must be to pass muster.” (p. 203)

“Another issue is the gap between legal recommendations, like those made in the American Bar Association’s “Criminal Justice Standards on Mental Health” (2016), and those understood by forensic evaluators in the field. […] An additional concern is whether forensic evaluators are asked to make a distinction between a defendant’s lack of pro se competence versus poor judgment in his or her case, or distinguish between a poorly conceived defense versus one heavily influenced by irrational thinking.” (p. 203)

“Yet another concern relevant to pro se competency is the conflict between two approaches pertaining to proper evaluation: whether evaluators should limit questioning to consider only if defendant has an understanding of “the implications of proceeding pro se (e.g., the rights waived and the ramifications of the waiver,”), or whether other, more nuanced abilities are also required for pro se competency. In an attempt to address this specific concern, mental health providers explored the importance of certain functional abilities with members of the court.” (p. 203)

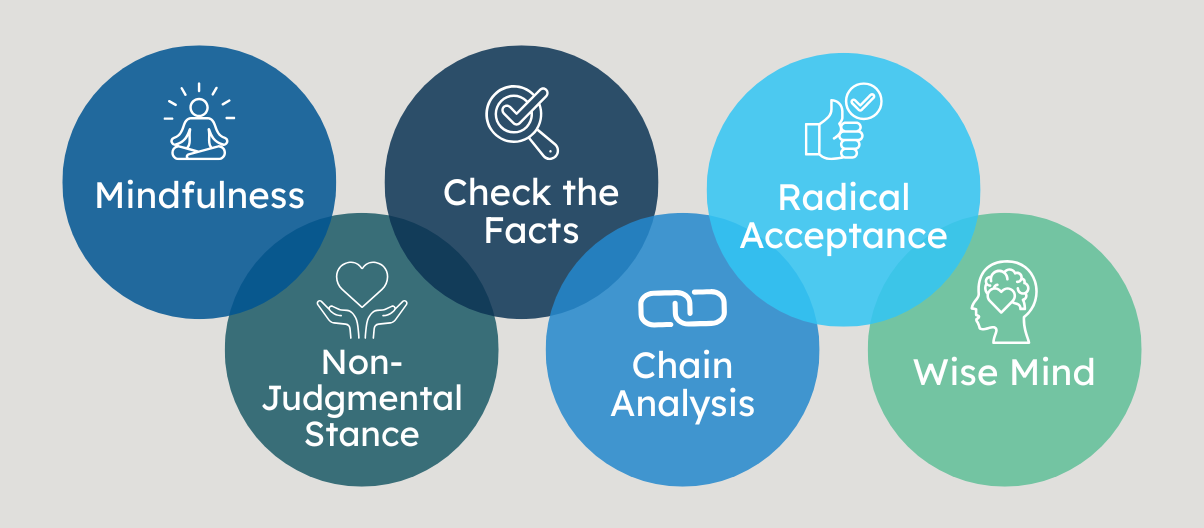

“Taken together, when asked to assess pro se competency, forensic evaluators should consider whether defendants can engage in rational decision-making and structured, organized, and goal-directed behaviors; have sufficient oral/written communication skills (and, if not, whether these difficulties can be ameliorated by translators, interpreters, or stand-by counsel); are able to conform their behavior to social/legal expectations; are able to monitor and modulate their emotions in a high-stakes environment; and have the prerequisite cognitive capacity to construct, mount, and modify an effective defense. An important prerequisite in many states is that any cognizable impairment must stem from a “severe” mental illness.” (pp. 203–204)

Translating Research into Practice

“Evaluators and lawyers must be aware of their state laws regarding pro se competency. […] Defense attorneys are advised, when faced with a client with possible mental deficits who indicates a desire to proceed pro se, to obtain an evaluation from a forensic mental health evaluator to determine if the decision was knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily made; if any decision to proceed pro se is influenced by mental illness; and if mental illness would likely undermine ability to represent oneself at trial. In particular, an attorney should request an evaluation when the attorney suspects that mental illness is infringing upon the client’s decision-making, communication, and case-specific abilities to proceed pro se.” (p. 207)

“If practicing in a state that requires functional abilities to proceed pro se beyond those necessary to stand trial, evaluators should have a set of questions designed to evaluate pro se competency. It should be noted that standardized instruments for competency do not sufficiently evaluate issues relevant to pro se. […] However, these instruments may provide useful information to the evaluator tasked to evaluate pro se competence. […] Clinicians tend to use a semi-structured interview because they need to evaluate the defendant’s abilities to make a knowing choice regarding the defendant’s specific case; to consider, understand, appreciate, and employ relevant information from that defendant’s legal information; to have appreciation for the current circumstances and the decision to self-represent; to be able to retain and rationally use necessary information; to be able to communicate coherently during courtroom proceedings; generate a rational legal strategy regarding that defendant’s specific case; and, communicate coherently with court personnel regarding his or her case.” (pp. 207–208)

“As a matter of consistent practice, evaluators may choose to screen for a defendant’s desire to proceed pro se (should the defendant mention the issue spontaneously before or during the competency interview) by asking questions about the defendant’s rationale for proceeding pro se, as well as his or her understanding of the benefits or disadvantages of doing so. This approach assesses the defendant’s abilities to understand relevant information, appreciate it in the context of his or her situation, reason, and communicate coherently, which potentially circumvents the need for the court to order a second competency evaluation, should the defendant formally raise the issue of self-representation at a later date. […] We caution evaluators against automatically assuming a defendant’s competency will remain static, and recommend consideration of pro se competency at multiple points throughout the trial process as needed.” (p. 209)

“An evaluator must assess whether a defendant’s mental illness would impede the ability to complete key tasks inherent in self-representation, such as generating a rational legal strategy, making an opening statement, and cross-examining witnesses. While evaluators should be very careful not to suggest a defendant should have advanced technical knowledge or legal skills in order to be competent to proceed pro se, it is also necessary to provide the court with information not only about the defendant’s reasons for self-representation, but also whether the defendant has the cognitive ability and basic understanding of key knowledge needed to do so. In light of this information, the judge (not the evaluator) may decide whether these abilities are relevant to pro se competency.” (p. 209)

“During an evaluation of pro se competency, evaluators may encounter beliefs about the case or about one’s attorney that are unlikely to be accurate but not delusional in nature. It is important to note that even the most delusional defendant may express beliefs about his or her case that are reasonable and not influenced by mental illness. For example, a defendant may express a desire for self-representation due to ineffective counsel or the belief they can “do it better.” When statements like these are made, the evaluator must probe them for their validity in order to determine the extent to which they are delusional. This may be accomplished by asking defendants to explain why they believe their attorneys are ineffective, or what behaviors they would expect an effective attorney to show.” (p. 209)

“Similarly, if a defendant describes several reasons he or she is able to act as his or her own counsel and these reasons are delusional or confusing (e.g., the defendant says everyone will listen to him/her in court because he or she is God’s messenger), these should be noted in the report and considered fundamentally distinct from more plausible rationales (e.g., the defendant says his or her attorney has a heavy caseload).” (p. 209)

“As noted above, many states have articulated vague legal standards relating to pro se competency. In addition, some have yet to decide whether to adopt a higher standard for self-representation than for competence to stand trial. Therefore, evaluators may receive little direction from courts when a defendant’s ability to proceed to pro se is at issue. Lawyers and mental health professionals should request guidance from the court if a pro se issue arises. In particular, they should ask (a) which capacities a defendant should have for self-representation, and (b) whether evaluators should consider impairments unrelated to a severe mental illness.” (p. 209)

“It is incumbent upon clinicians tasked with these evaluations to be aware of the standard set forth in their jurisdiction and adapt their evaluations accordingly. Clinicians need to remain cognizant of relevant changes that should alter their practices of assessing pro se competency consistent with jurisdictional requirements. In making adaptations for pro se competence, clinicians may start with a standard assessment measure, but must then move to individual-based assessments.” (p. 210)

Other Interesting Tidbits for Researchers and Clinicians

Some of the questions that can be asked as a way to assess competency in regard to self-representation include: “Why do you want to represent yourself?”, “If you decide that you want to represent yourself, what does this mean you must be prepared to do in the courtroom? That is, how would you plan to go about representing yourself?”, “What do you think you might plead and why? If a defendant actually committed the crime, is he/she allowed to plead not guilty—and when might a defendant consider doing this? (After presentation of a series of plea bargains for a hypothetical defendant): What do you think of these suggestions for the defendant in the story? Would you consider these deals and why/why not?”, “What are the benefits of representing yourself? What are the disadvantages?”, “If you proceed pro se, a stand-by attorney may be provided to assist you as needed. Could you work with this person? Do you have any reservations about doing so?”. (p. 208).

“[These questions are] intended to guide an evaluator’s examination, but has not undergone empirical validation. These questions may be added to an existing competency interview/protocol, or they may be made into a separate pro se competency interview, depending on the evaluator’s preference and state guidelines.” (p. 208)

Join the Discussion

As always, please join the discussion below if you have thoughts or comments to add!